Research undermines panic of automation displacing trucking jobs

While some stakeholders are panicking over the potential mass displacement of trucking jobs due to automation, researchers at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics are more optimistic. A recent study suggests that the idea of millions of lost trucking jobs is “overstated.”

Maury Gittleman, research economist for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Kristen Monaco, associate commissioner for Compensation and Working Conditions for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, recently published a study titled “Truck-Driving Jobs: Are They Headed for Rapid Elimination?”

The short answer to that question is “no.”

Researchers reached that conclusion based on three factors:

- The number of truckers is “inflated due to a misunderstanding of the occupational classification system used in federal statistics.”

- Truckers’ skills other than driving will always be in demand.

- Some trucking segments will be more difficult to automate than others.

That’s the good news for truckers in general. However, there is some bad news for long-haul truckers.

“Long-haul trucking (which constitutes a minority of jobs) will be much easier to automate than will short-haul trucking (or the last mile), in which the bulk of employment lies,” the reports states.

The study surmises that thousands, not millions, of trucking jobs may be at a limited risk as a result of automation.

How many truckers are there?

According to the study, there are far fewer than 3 million truck drivers, as is often reported. So when people like presidential candidate Andrew Yang claim millions of trucking jobs are at risk, that may not be the case.

The study points to how jobs are classified. When people refer to the more than 3 million trucking jobs, they are likely referring to occupation code 53-3030, which is for “Drivers/Sales Workers and Truck Drivers.” In addition to “heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers,” “driver/sales workers” and “light truck or delivery services drivers” are also included.

In 2016, there were 3 million employees in that category. However, tractor-trailer truck drivers accounted for only 1.7 million of those jobs. Excluded from that data is the number of long-haul versus short-haul drivers. The number of self-employed owner-operators versus company drivers is also excluded.

Furthermore, the requirements for all jobs included within the 53-3030 code range from no experience to a Class A CDL. According to the study, only 16% of driver/sales jobs and 27% of light truck/delivery jobs require previous experience. On the other hand, nearly two-thirds of heavy truck driver jobs require experience.

Accordingly, stating that 3.5 million truck million jobs could be lost to automation is not only a broad, sweeping generalization of a diverse occupational category, but it also grossly overestimates the potential number of actual truck driving jobs at risk.

More to trucking than driving

The report also highlights that even if trucks themselves become fully automated, there are still a variety of tasks that truckers perform that go beyond driving duties of a vehicle.

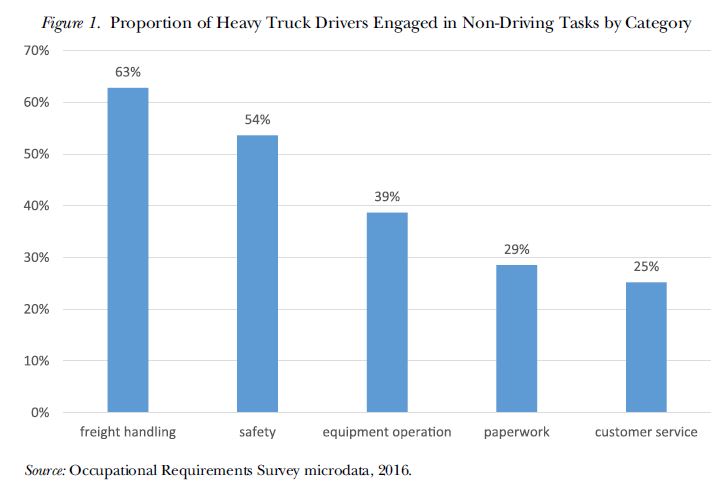

One source cited listed top tasks for truckers as checking vehicles, following safety procedures, inspecting loads, maintaining logs and securing cargo. The below chart shows the prevalence of non-driving related tasks:

Can robots do the above tasks?

“Many of these nondriving tasks are not immediately automatable,” researcher state. “Currently there exists no widespread testing of technology used to load or unload trucks, which is the task set that drives the strength requirements in the Occupational Requirements Survey. Although equipment (such as pallet jacks) tends to be used to assist in these activities, it mitigates some of the strength requirement but does not automate the action of loading or unloading.”

Even though such visual tasks like checking for unbalanced loads and low tire pressure can be done through sensors, correcting those issues still require a human to perform.

Although the Occupational Requirements Survey has the lowest educational requirement listed for material-moving occupations, it does not mean there are no barriers to entry. Specific vocational preparation, the amount of time needed to reach an average level of performance, tells a different story.

For tractor-trailer drivers, more than three-quarters of jobs require one month to four years of vocational prep. Nearly half of that prep time is within the one-to-four-year range. Compared to the rest of the economy, more than a third of all jobs require no more than one month of vocational prep time.

When it comes to decision making, 77% of tractor-trailer driving jobs require a “straightforward decision from set choices,” and 16% of drivers need to “assess situations and possible outcomes,” suggesting a more complex level of cognitive thinking required.

Physically, trucking is no easy task. The Occupational Requirements Survey ranks jobs by strength needed into five categories: sedentary, light, medium, heavy and very heavy. Among tractor-trailer trucker jobs, more than 80% require medium or heavy strength, with 42% requiring heavy strength. Comparatively, 38% of all jobs fall into the sedentary or light categories.

Which trucking jobs are more vulnerable to automation?

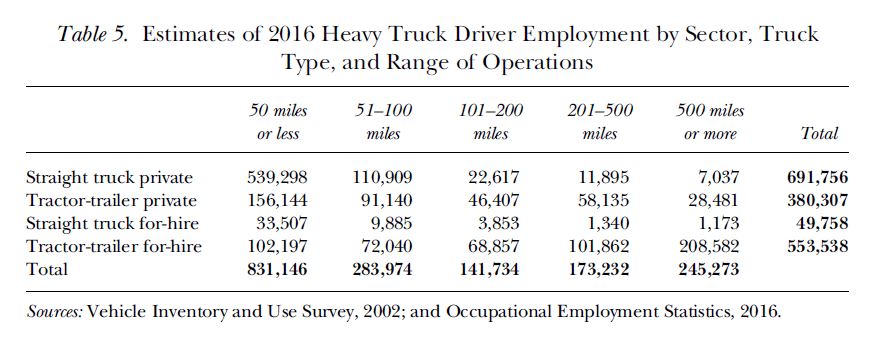

After establishing there are closer to 1.7 million trucking jobs than more than 3 million, the report looks into how many of those 1.7 million jobs are at risk. Unfortunately, there is no reliable data that shows the specific operations (e.g., long haul versus short haul) of each trucking job.

Using the Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey, researchers broke down how many truckers drive the following distances:

From here, researchers assume that long-haul trucking is most likely to be affected by high-automation vehicles. This assumption is based on the business models of companies such as Starsky Robotics and Waymo. Those companies focus on highway mileage and having a human driver perform “first and last mile” driving tasks.

Even if automation takes over the highways, there will still be a need for trained drivers elsewhere. Needless to say, trucking operations will drastically change.

“The first- and last-mile problem, then, has the potential to mitigate some of the displaced labor since driving skills are still needed, but perhaps in different locations than before,” the study states. “It may also lead to a modification in the nature of truck operations, which have been largely unchanged since industry deregulation of the late 1970s and early 1980s gave rise to separation between truckload and less-than-truckload operations.”

However, that is only considering the operational limitations of automation. Researchers also discussed practical limitations of automation.

More specifically, the study notes that trucks break down all the time. To address this, an infrastructure servicing broken down trucks needs to be built. Additionally, companies will have to address cargo theft. What will be done to protect cargo once a driverless truck breaks down?

Furthermore, there is a long list of regulatory hurdles to clear. Currently, few states have laws regulating self-driving vehicles. Even if most states establish some regulations, interstate trucking is regulated federally, throwing another wrench into the situation.