Requiem for Mr. Arthur

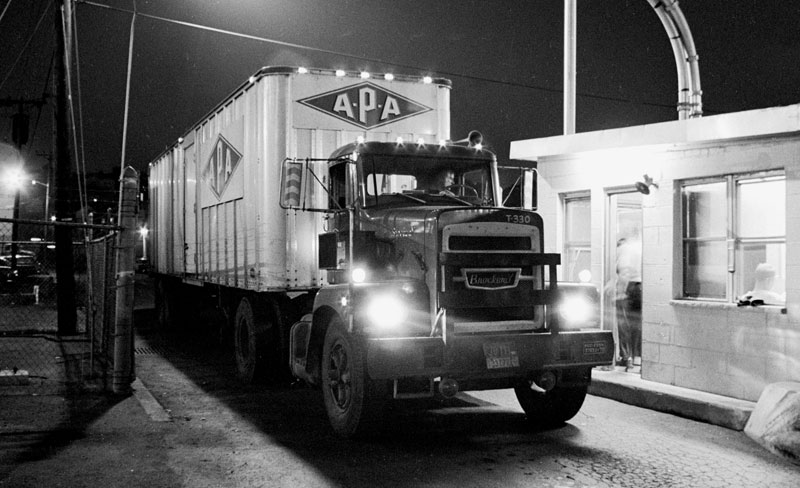

Arthur Imperatore was a big man in trucking though the ’60s and ’70s and into the 1980s. He’s famous – more or less – for starting New York Waterways, which restored long-gone commercial ferry service to New York harbor. Well before that, though, he created A-P-A Transport Corp., the highly profitable Northeast LTL that became a model for others in the ’60s and ’70s.

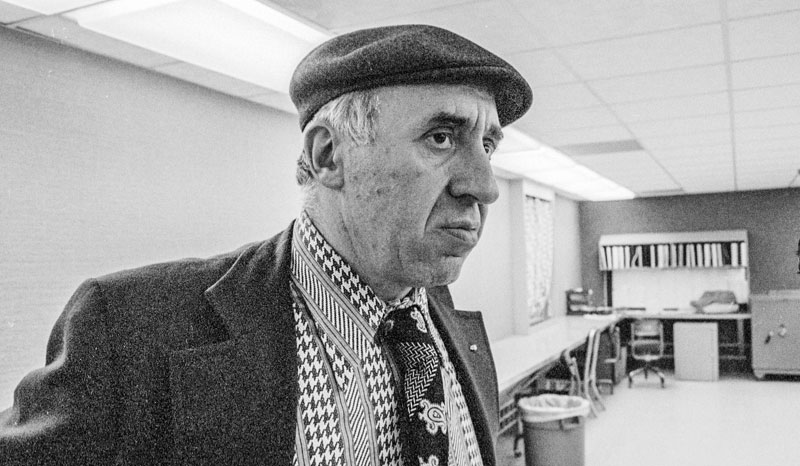

Arthur was an imposing, forceful man with the bearing of a general. Four-star Gen. George S. Patton comes to mind. You did not argue with Gen. Patton, and you did not argue with Arthur Imperatore. His Teamster drivers and dock men called him Arthur. To everyone else at A-P-A, he was Mr. Arthur, a boss who didn’t like to be crossed.

Once he fired a driver for drinking on the job. The union took it to arbitration, where the driver was reinstated. Arthur was so pissed he showed up in the North Bergen drivers’ room the next morning, stood on a table, and told the drivers about the arbitrator’s decision.

If one guy was going to get away with drinking, it was only fair that everyone be able to drink, he said. Arthur said drivers leaving by one gate could pick up Ballantine Beer. At another, they could get Schlitz. A few drivers laughed, but only a few. Arthur’s bitter sarcasm and muted fury engulfed the room. The laughing faded into to the sound of shuffling feet and the occasional cough.

Arthur had grit, no doubt about it.

Once A-P-A had three drivers loading trailers at a Jersey City warehouse. Arthur decided to swing by to make sure his guys were working. As he walked onto the platform, a driver for Hemingway, another LTL, commented on Arthur’s hat. It was probably a good-natured joke, but Arthur was not in a good-natured mood. He demanded an apology. The Hemingway driver, now challenged, said no. Arthur grew more demanding. Pushing turned to shoving, and finally fists flew. The Hemingway driver connected first, and Arthur went down. He got up again. Hemingway knocked him down again. The Hemingway driver pleaded with Arthur to stay down or call the fight off, but Arthur got up again, only to be decked a third time.

It was the Hemingway driver who broke. As Arthur struggled to get up again, his face bloodied, Hemingway had enough. OK, OK, he said, and apologized for the hat remark. (Sounds like the fight in “Cool Hand Luke,” I know, but that’s how the story is told, and it predates the movie by a decade or so.)

Later that day back at the terminal, Arthur demanded to know why, when he had three men on the platform in Jersey City, no one helped him. “Pappy” Petsch, the most senior of the three answered.

“We was workin,’” he said.

Arthur’s determination didn’t always work to his advantage. In the winter of 1977, as a snowstorm began in the early morning hours, Arthur was pissed by the school and business closings announced on the radio. The country was going soft, he told Sam DePiano, the North Bergen terminal manager. Sam suggested they cancel operations. Arthur refused. A-P-A was an aggressive, virile company that got the job done and would operate as usual, snow or no snow, Arthur explained.

Many snowbound drivers called out, but most managed to show up. It was bad out there, they cautioned. Arthur wouldn’t listen. The handful of 7 a.m. starters headed out with only a few instances of spinning wheels at the very top of the hill at Tonnelle Avenue. After they had left, the storm turned to blizzard. Then the 8 a.m. starters – most of the fleet – began leaving.

Drivers could barely see each other in the thick snow, and the streets that led to Tonnelle Avenue – the only way out to the world – were in bad shape now.

While the 7 o’clock trucks had cleared the half-a-block hills leading to Tonnelle Avenue, the 8 o’clock trucks could not. Trucks that almost made it to Tonnelle Avenue had slid back into trucks midway up. By 8:15 a.m., trucks behind the slippers and sliders on the hill were lined up all the way back into the terminal.

Arthur did not give in until dispatch began getting calls from drivers who had made it out. Most were stuck somewhere. Backing all those trucks into the terminal took more than an hour. Since the drivers who had punched in – whether they got out of the yard or not – were owed eight hours pay according to the Teamster contract. Arthur’s tough-guy decision cost A-P-A a lot of money.

Imperatore nurtured A-P-A during the 1950s and ’60s in the densely packed neighborhoods of Hudson County, N.J., where rigid, often corrupt unions ruled. An overbearing Interstate Commerce Commission stood just beyond the unregulated commercial zone of New York City, ready to prevent any upstart trucker from serving even the nearby suburbs, never mind adjoining states.

Imperatore stood up to unions, honoring contracts but demanding that his workers honor their obligations.

He required – and for the most part he got – an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay. He painstakingly bought into nearby markets, acquiring operating rights from carriers who were less successful. Back then, it was the only way to expand.

For many years Imperatore was so cautious about new hires that he insisted on interviewing every potential new driver personally. Candidates reached that final interview only after a 15-day on-the-job trial, a thorough physical, a lie-detector test, handwriting analysis and who knows what else. Only with Imperatore’s personal OK could you punch in for a 16th day and gain a spot at the bottom of A-P-A’s seniority list.

My near six years at A-P-A began in December 1967. I finally got my interview with Arthur Imperatore early in 1968. In the 52 years since then I’ve had struggles and my share of victories, but no victory in memory remains as sweet as the day Arthur gave the nod and I made the list at A-P-A.

Arthur Imperatore died Nov. 18 at the age of 95. LL