How can the trucking industry avoid nuclear verdicts?

An American Transportation Research Institute study reveals that eight-figure jury verdicts against trucking companies are skyrocketing. However, the real eye-opener deals with why truckers are losing the battle and how they can avoid these nuclear verdicts.

Recently, ATRI published a study called “Understanding the Impact of Nuclear Verdicts on the Trucking Industry.” It is chockful of information detailing how the price tag of jury verdicts is increasing at an alarming rate.

It’s worth noting that less than 1% of truck-involved crash cases exceed $750,000, the current insurance minimum. ATRI narrowed its focus on the headline-grabbing cases that trial lawyers and certain lawmakers are using to state their case for minimum insurance increases. Although ATRI’s research does verify that nuclear verdicts are rising in value, that does not necessarily mean the percentage of crash cases ending in nuclear verdicts is increasing.

A lot of publications, including mainstream media, are reporting about the numbers. But “hidden” inside the 82-page study is a section that dissects the methods injury attorneys use to win cases, despite a mountain of evidence that should lead a logical and reasonable jury to the opposite conclusion.

Increase in nuclear verdicts

First, let’s take a quick glance of the study’s data of nuclear verdicts. Perhaps many, if not most, trucking stakeholders suspected the increase, but ATRI did a wonderful job of quantifying these suspicions.

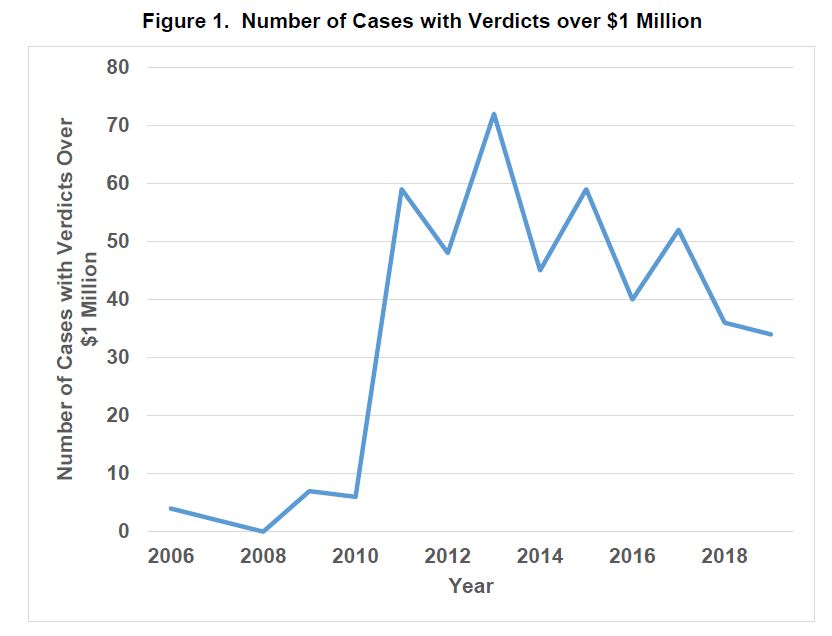

According to the study, jury verdicts of more than $1 million have increased significantly in the past 14 years. Of the 600 cases analyzed only four with verdicts of more than $1 million were found in 2006. However, 2013 saw a peak of 70 such cases. From 2010 to 2013, the number of seven-figure verdicts went up by about nine times, sustaining that level ever since.

A quick scan of the first 25 pages of the study details this increase of nuclear verdicts. The bottom line: Juries are hitting trucking companies with insanely (and increasingly) large verdicts.

But what about inflation and healthcare costs? Surely increases in those two factors played a role, right? Wrong. Check out the graph below:

Although inflation and healthcare costs have certainly gone up, the increase rate of jury verdicts is exceedingly larger. When inflation and healthcare costs are accounted for, the average large verdict increased during this period between 36.5% and 37.6% faster than inflation or healthcare costs, the report states.

So what is driving up these nuclear verdicts?

Tugging at the heart strings

If inflation and healthcare costs cannot explain the increase in nuclear verdicts, then one can assume the bulk of that money is going to noneconomic and punitive damages. These are the “pain and suffering” and punishment costs.

When it comes to a jury trial and nuclear verdicts, it really does not necessarily matter what the facts are.

It comes down to which attorney can convince six to 12 randomly selected citizens to side with them.

For example, ATRI’s study reveals that verdicts in cases where no children are involved yielded an average of $2.3 million.

However, when a child is introduced to the equation, the number shoots to $42.3 million.

That is a 1,687% increase. It is not like you have to factor in loss of income for a child. The study attributes, at least partly, this increase to “contributions during minority.”

According to a Notre Dame Law Review article, these are contributions “the child would have made in the form of earnings or services during his minority from the date of death” or injury. One would think that a child is an economic cost, not an economic asset. However, the child’s sex, intelligence, personality, health and character can be factored in.

“Courts in increasing numbers are displaying favor toward higher awards in child death cases, and often indulge in semantic gymnastics to justify a substantial award within the framework of this rule. … As a practical matter, juries in such cases make an award based mostly on sympathy, and the court permits as much of it to stand as it thinks can be squeezed within the confines of the rule,” the article states. “Naturally, a great deal of speculative evidence is considered. The whole process is awkward and the results unfavorable because this pecuniary rule of damages is a legal fiction.”

Spinal injuries also result in nuclear verdicts.

This is likely because of the life-changing nature of such injuries. These emotional factors can rile up a jury to further punish the trucking company with punitive damages. Combine noneconomic damages with punitive damages, and you have a nuclear verdict.

How can the trucking industry avoid nuclear verdicts?

In a perfect world, logic wins over emotion. In reality, that is not always the case, especially in the courtroom. Perhaps, there is a lesson here for attorneys representing the trucking industry in crash litigation.

There is a lot of data that suggest truckers are not usually the cause of fatal crashes. However, ATRI’s nuclear verdict makes it seem the opposite is true.

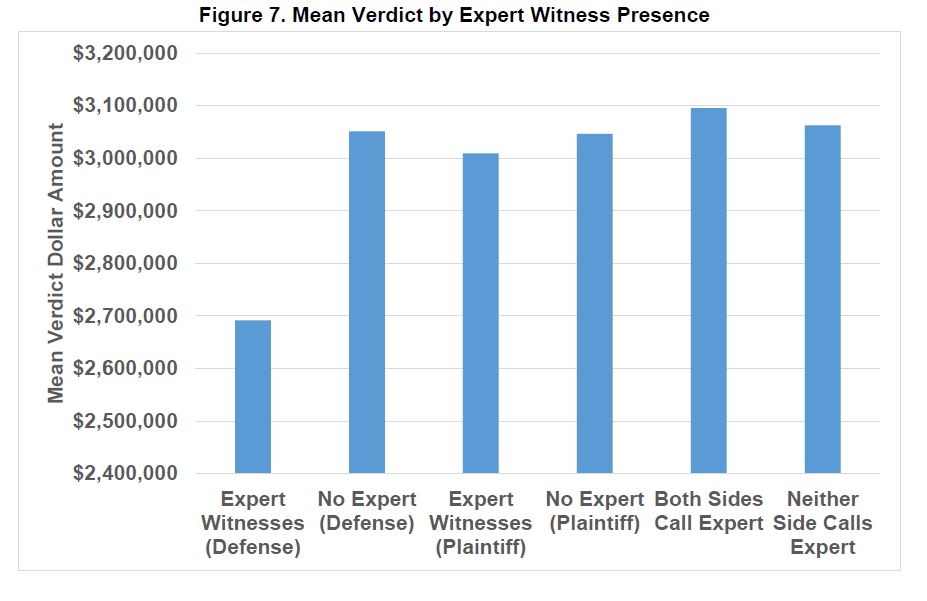

For example, take a look at this graph detailing verdict size in relation to expert witnesses:

One would think that cases where only the plaintiff calls an expert witness would have the largest verdict. However, the data reveals that cases with either both sides or neither side having an expert witness have the largest verdict. In other words, even on a level playing field, the trucking industry gets hit the hardest.

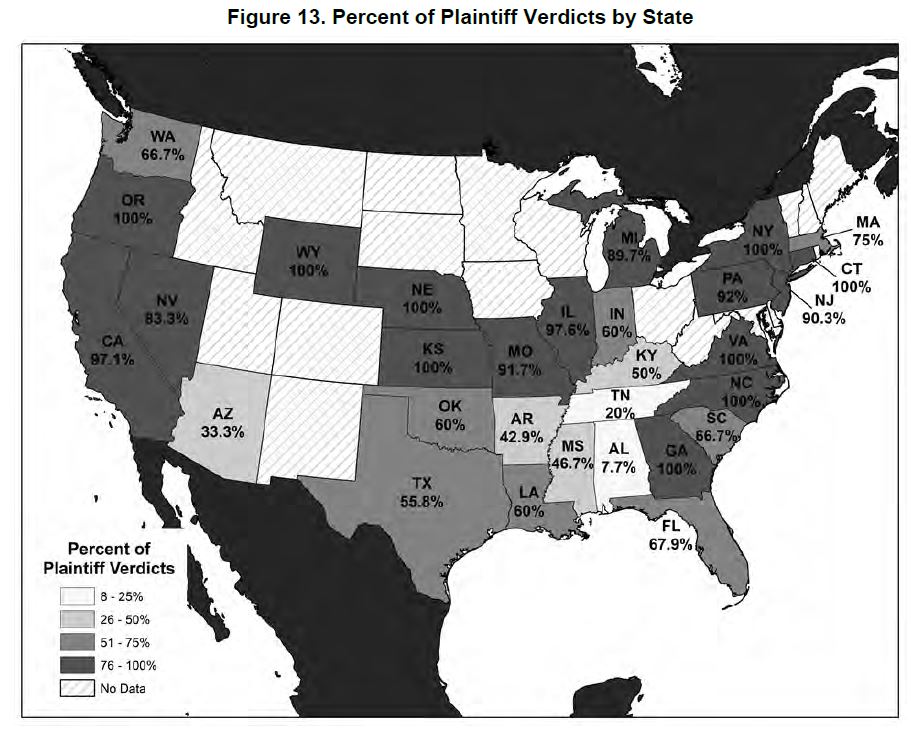

Perhaps more telling is the map showing the plaintiff win rate by state:

Look at how many states have a plaintiff win rate of more than 90%. Are truckers responsible for 90% of all truck-involved fatal crashes in those states?

It appears that the trucking industry is losing cases that it should be winning.

So how can the industry avoid these nuclear verdicts? A possible solution can be found about halfway into ATRI’s research.

“Another issue cited by interviewees is the strategies employed by both sides in preparing for a trial, and, at its simplest, it is striking a balance between facts and emotion,” ATRI said.

It comes down to logos and pathos, i.e., logic and emotion. ATRI defined logos as “persuasion through the building of a logical, empirical construct. Used appropriately, logos is ostensibly technically or scientifically irrefutable”

On the other hand, pathos is defined simply as an appeal to emotion. ATRI states that “pathos is the most powerful or effective form of rhetoric, based on psychology and human nature.”

And therein lies the answer.

In simplest terms, defense attorneys might consider sinking to the level of the plaintiff’s attorneys.

When faced with a lawsuit seeking a nuclear verdict, rather than use logic to win, tug at the heartstrings of the jury.

Defense attorneys should let the jury know that they are representing a human being too. A nuclear verdict can destroy the life of an owner-operator by driving him or her out of business. Consequently, they go broke, and their entire family is in dire straits. Essentially, the jury is correcting the livelihood of one human by destroying the livelihood of another. That is not justice.

In fact, ATRI gave an example on how this can be accomplished:

Interviewees referenced other approaches that can be more tactical or strategic, including the application of the reptile theory, sentiment, and humanizing the defense (motor carrier). The reptile theory asserts that an attorney influences a jury by appealing to the reptilian complex, a portion of the brain that controls breathing, heart rate and other functions associated with survival. When the reptile theory is applied in a legal setting, questions are framed in a way that compels the jurors to make decisions based on fear or survival instinct, rather than logic and reasoning. For example, an attorney may present a safety scenario as being potentially catastrophic to anyone on the road, and convince jurors that they can make everyone safer by punishing the defendant with a large verdict.

Anyone who is on social media can confirm that logic and reasoning do not always win. Emotion can override that part of the brain. The people who are on social media are the same people being called for jury duty. Sometimes, you have to fight fire with fire.